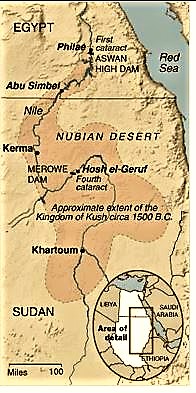

Archaeologists are finding widespread evidence that the kingdom of Kush once had influence over a 750-mile stretch of the Nile Valley.

For five centuries in the second millennium B.C., the kingdom of Kush flourished with the political and military prowess to maintain some control over a wide territory in Africa.

On the periphery of history in antiquity, there was a land known as Kush. Overshadowed by Egypt, to the north, it was a place of uncharted breadth and depth far up the Nile, a mystery verging on myth. One thing the Egyptians did know and recorded — Kush had gold.

Some archaeologists theorize that the discoveries show that the rulers of Kush were the first in sub-Saharan Africa to hold sway over so vast a territory.

This makes Kush a more major player in political and military dynamics of the time than we knew before,” said Geoff Emberling, co-leader of a University of Chicago expedition. “Studying Kush helps scholars have a better idea of what statehood meant in an ancient context outside such established power centers of Egypt and Mesopotamia.”

Over the last few years, archaeological teams from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Sudan and the United States have raced to dig at sites that will soon be underwater. The teams were surprised to find hundreds of settlement ruins, cemeteries and examples of rock art that had never been studied. One of the most comprehensive salvage operations has been conducted by groups headed by Henryk Paner of the Gdansk Archaeological Museum in Poland, which surveyed 711 ancient sites in 2003 alone.

This area is so incredibly rich in archaeology,” Derek Welsby of the British Museum said in a report last winter in Archaeology magazine.

In Sudan, the Merowe Dam, built by Chinese engineers with French and German subcontractors, stands at the downstream end of the fourth cataract, a narrow passage of rapids and islands. The rising Nile waters will create a lake 2 miles wide and 100 miles long, displacing more than 50,000 people of the Manasir, Rubatab and Shaigiyya tribes. Most archaeologists expect this to be their last year for exploring Kush sites nearest the former riverbanks.

Gold was already known as a source of Kush’s wealth through trade with Egypt. Other remains of gold-processing works had been found in the region, though none with such a concentration of artifacts. Dr. Emberling said that more than 55 huge grinding stones were scattered along the riverbank.

Thank you for sharing N.G.!

Experts in the party familiar with ancient mining technology noted that the stones were similar to ones found in Egypt in association with gold processing. The stones were used to crush ore from quartz veins. The ground bits were presumably washed with river water to separate and recover the precious metal.

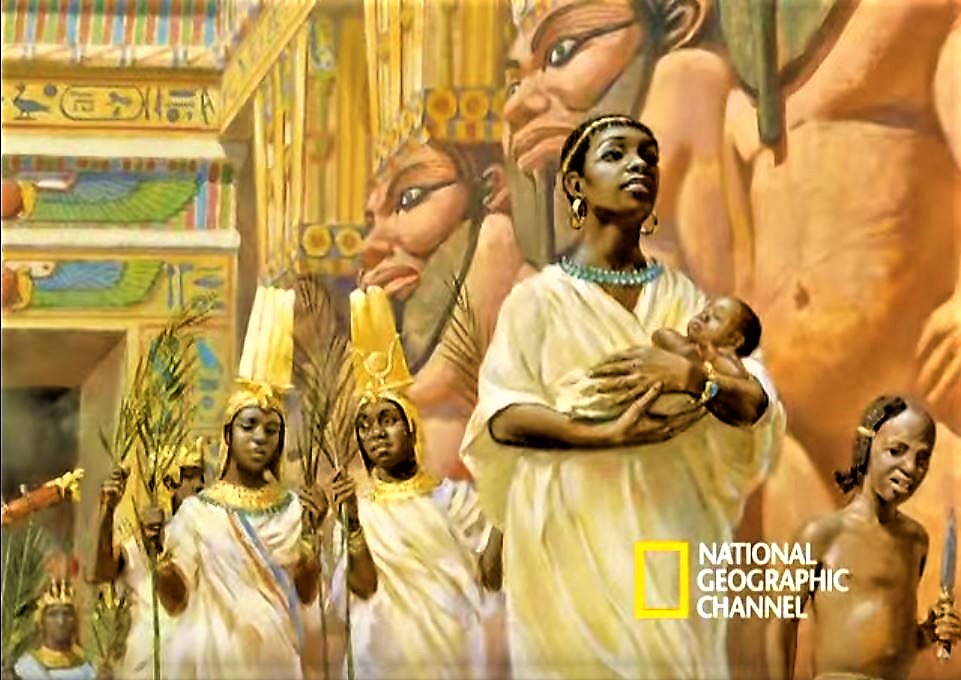

The cush Empire also gave women more political power than did most other ancient empires. In fact several cush monarchs were women.

“Even today, panning for gold is a traditional activity in the area,” said Bruce Williams, a research associate at the Oriental Institute and a co-leader of the expedition.

But the archaeologists saw more in their discovery than the glitter of gold. The grinding stones were too large and numerous to have been used only for processing gold for local trade. Ceramics at the site were in the style and period of Kush’s classic flowering, about 1750 B.C. to 1550 B.C.

This appeared to be strong evidence for a close relationship between the gold-processing settlement and ancient Kerma, the seat of the kingdom at the third cataract, about 250 miles downstream. The modern city of Kerma has spread over the ancient site, but some of the ruins are protected for further research by Swiss archaeologists, whose work will not be affected by the new dam.

British and Polish teams have also reported considerable evidence of the Kerma culture in cemeteries and settlement ruins elsewhere upstream from the fourth cataract. Near Hosh el-Geruf, the Chicago expedition excavated more than a third of the 90 burials in a cemetery. Grave goods indicated that these were elite burials from the same classic period and, thus, more evidence of the influence of Kerma. A few tombs had the rectangular shafts of class Kerma burials, graceful tulip-shaped beakers and jars of the Kerma type and even some vessels and jewelry from Egypt.

“The exciting thing to me,” Dr. Williams said, “is that we are really seeing intensive organization activity from a distance, and the only reasonable attribution is that it belongs to Kush.”

The primary accomplishment of the salvage project, the archaeologists said, is the realization that the kingdom of Kush in its heyday extended not just northward to the first cataract, but also southward, well beyond the fourth cataract. At places like Hosh el-Geruf, they added in an internal report, “the expedition found the Kushites’ organized search for wealth illustrated in a significant new way.

–Archaeology – Kingdom of Kush – Egyptian Civilization – The New York …

They develpoed their own written language

The remains of extensive iron industries form prominent features at key locations within the Meroitic landscape, demonstrating the significance of iron production within the history of this period of the Kingdom of Kush. The iron industries would have involved a large portion of the population at Meroe, from those who went to the hills to collect the ores, to those who made the charcoal, to those who smelted the iron in distinctive furnace workshops. The products of these industries, iron tools, weapons, architectural implements and adornments, would have had a major impact on the rise and success of the kingdom. Thus by unravelling the secrets of these industries we will reveal much about the social, economic, political and religious contexts of Kush. However, when this new research project was launched in 2012, despite Meroitic iron production being often discussed within the academic community, knowledge of this fundamental Meroitic industry was notably superficial.

In addition to a significant (and largely unexplored) archaeometallurgical potential, there exists an emotive debate as to whether iron production in fact entered sub-Saharan Africa from Meroe, or was instead independently invented at one or more locations to the south and/or west. Hence this new research, the first in decades to attempt to understand of Meroitic iron technologies, will both generate data from which a much enriched view of the role and impact of technology during Meroitic times, and allow for a broader consideration of the position of Meroitic iron production within debates surrounding the origins of iron in Africa.

Dr Jane Humphris, head of the UCL Qatar research in Sudan, which focuses on the remains of ancient industries, first travelled to the Meroitic site of Hamadab in Sudan in 2012 to join the ‘Hamadab and Meroe Royal Baths’ project of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI). Led by Dr Pawel Wolf, archaeological research at the site of Hamadab has been ongoing for a number of years, and continues to reveal much about life at this urban settlement. One aspect of the site that had remained unexplored until now are the extensive remains associated with a major iron producing industry.

Excavating the biggest slagheap at Meroe Royal City.

The fieldwork began with an extensive ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey. The results of this survey were combined with data produced during a pervious magnetometer survey, in the hope that the locations of ancient furnaces would be revealed. In total, six large trenches were excavated both within and close to the iron production remains, and nearly 700 archaeometallurgical and associated archaeological samples were collected and shipped to UCL Qatar for laboratory analysis. These samples included numerous charcoal samples which were collected for wood species identification and radiocarbon dating. A thermo- and optically stimulated luminescence dating strategy was also implemented.

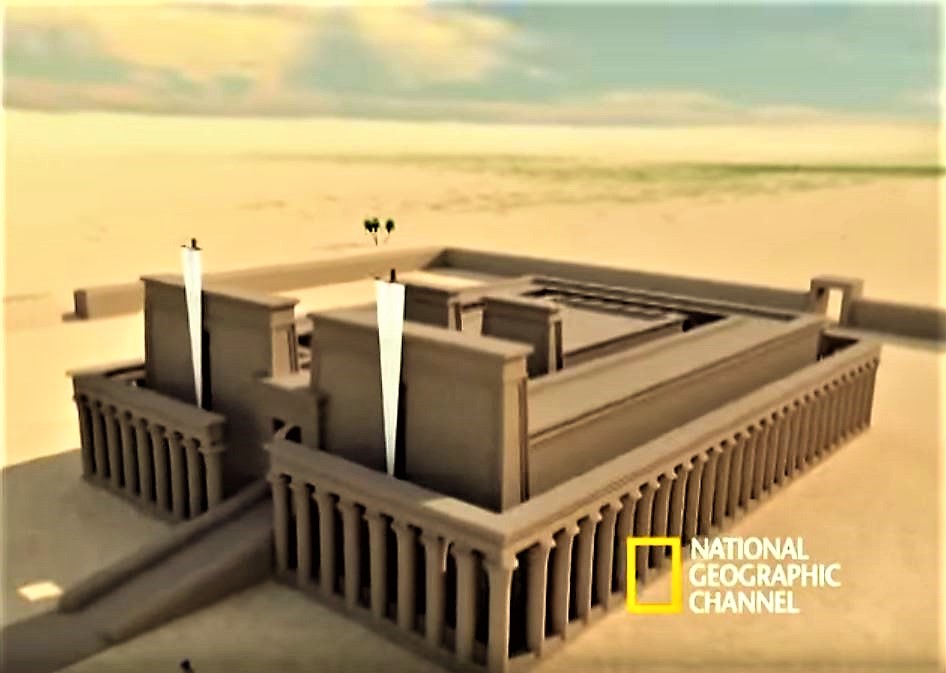

Large-scale excavations were carried out at a number of locations in the Meroe region. At Meroe Royal City, the team completed the excavation of an ancient furnace workshop, found by the team using geophysics techniques described above, the year before. This is the first Meroitic furnace workshop found since the 1960’s, and therefore the only one to ever be excavated using modern techniques and scientific analysis. The data being generated from geochemical analysis will help us to understand the operating parameters of the workshops and further help us to understand how the iron smelters worked and the materials they used. Also at the Royal City, an extensive excavation at the Apedemak Temple which is situated on top of an iron producing area, revealed not only a new Meroitic building and a 10m long, 3m tall section through the slag heap, but also a retaining wall surrounding the metallurgical remains and other insights into the relationship between the industrial evolution of the site and the more general religious and political context of the time. Further excavations will take place at both of these exciting locations during the coming seasons of field work.

Finally, during an exploration of the wider region for possible iron ore sources that may have been used by the ancient smelters, the team, led by an elderly Sudanese gentleman, may have found the ancient mining area of the Meroites, situated approximately 10km away from the Royal City. A pragmatic survey was carried out which revealed burnt bricks, occasional pottery and slag, and even a fragment of a carved statue, all found amongst dozens of silted up depressions across a large hilltop. Two test excavations were carried out to understand these depressions further, and extensive aerial mapping and excavations are planned for the coming field seasons.

No Comments Yet