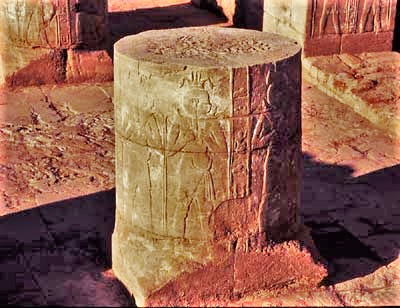

Archaeologists excavated a sprawling temple complex dedicated to the god Amun at the Sudanese site of Dangeil.

Egypt’s most important and enduring relationship was, arguably, with its neighbor to the south, Nubia, which occupied a region that is now in Sudan. The two cultures were connected by the Nile River, whose annual flooding made civilization possible in an otherwise harsh desert environment. Through their shared history, Egyptians and Nubians also came to worship the same chief god, Amun, who was closely allied with kingship and played an important role as the two civilizations vied for supremacy.

Ram’s-head Amulet

Representations show these pharaohs wearing a ram’s-head amulet tied around the neck on a thick cord.

Rams were associated with the god Amun, particularly in Nubia, where he was especially revered.

–Sudan, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D. | Chronology | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art …

During a period of discord in Egypt, the Kushite king Piye first secured Amun’s northern home, in Karnak, Egypt. Then, claiming to act on the god’s behalf to restore unified control of Nubia and Egypt, he conquered the rest of Egypt and, in 728 B.C., became the first in a line of Kushite pharaohs who ruled Egypt for around 70 years.

The cult of Amun remained central to religion—and politics—in Nubia for centuries to come. This has been illustrated by the findings of an excavation in Dangeil, a royal Kushite town on the banks of the Nile south of Napata. The excavation, which has been carried out since 2000 with support from Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, the British Museum, and the Nubian Archaeological Development Organization (Qatar-Sudan), has turned up evidence of what may have been a series of temples to Amun that stood on the same location for around a thousand years in all—from the period when Kushite pharaohs ruled Egypt to the first few centuries A.D., when Kushite civilization entered a new golden age and Egypt served as a Roman colony.

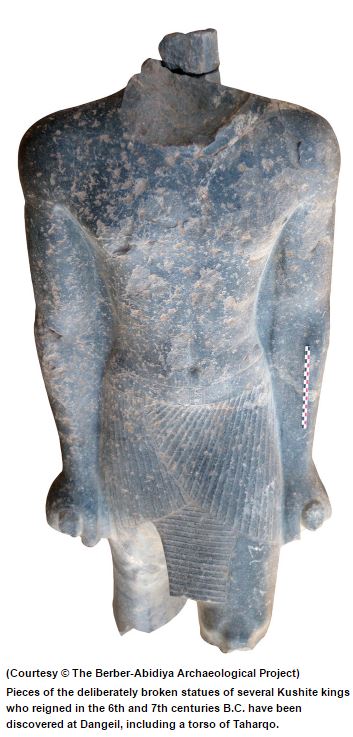

At Dangeil, archaeologists have found fragments of statues of at least three Kushite kings who ruled during the sixth and seventh centuries B.C., along with evidence of a monumental structure they believe might have been a temple to Amun dating to the same period. The earliest of these kings is Taharqo, one of the Kushite pharaohs, who ruled Nubia and Egypt from 690 to 664 B.C. Intact, Taharqo’s statue would have stood almost nine feet tall. Inscribed on a belt on one of the statue’s recovered fragments are Egyptian hieroglyphs that read: “The perfect god Taharqo, beloved of Amun-Re.” Indeed, Kushite kings during this period were considered sons of Amun, and it was believed the god would select new kings through his priests.

Coronation took place at the temple at Jebel Barkal, after which the new king would visit other temples to Amun and then build new ones and renovate old ones—all steps taken to establish the king’s connection to the god and affirm his right to rule. The territories covered could be vast.

Head of a Ram · The Walters Art Museum · Works of Art

Taharqo was a particularly ambitious leader in this regard who presided over a kingdom that extended as far north as Palestine. He renovated and built temples throughout Egypt and Nubia, perhaps even the possible temple to Amun in Dangeil. Dangeil is the farthest south a colossal statue of Taharqo has been discovered, suggesting that it may well mark the southern extent of his kingdom. Over time, Kushite control extended even farther south, and, by the third century B.C., the capital is thought to have moved from Napata to Meroe, south of Dangeil.

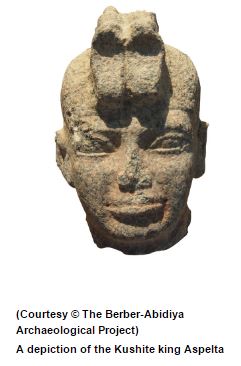

Kushite rule over Egypt reached its height under Taharqo, but his reign ended in defeat, with Egypt largely lost to Assyrian invaders. Ultimately, the Nubian expulsion from Egypt was completed under Taharqo’s successor, Tanutamun (r. ca. 664–657 B.C.). The other Kushite kings whose statues were found at Dangeil are Senkamanisken (r. ca. 643–623 B.C.) and probably Aspelta (r. ca. 593–568 B.C.). Hieroglyphs on the back of the Senkamanisken statue identify him as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” suggesting that despite having been kicked out of the country decades earlier, the Kushites still saw themselves as the rightful rulers of Egypt. However, any designs they might have had on reconquering Egypt were snuffed out around the beginning of Aspelta’s reign.

The statues of the kings found at Dangeil were intentionally broken at the neck, knees, and ankles, but were not defaced. Caches of statues of the same kings, and a few others, all broken in a similar manner, have also been found at Jebel Barkal and another location in Nubia.

Head of a ram | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

On the same site in Dangeil where they believe a temple to Amun may have stood starting around the seventh century B.C., the archaeologists have found far more extensive evidence of a temple to Amun dating to the first century A.D. It has the same directional orientation as the earlier building and used some of its walls as foundations. According to Anderson, this suggests that the earlier building was probably still functioning when it was replaced. This later temple was likely built during the reign of Queen Amanitore and her co-regent Natakamani, a period of peace and prosperity remembered as a golden age of Kushite civilization. A war with the Romans, who had by this time colonized Egypt, had come to an end around 20 B.C. with a nonaggression pact and resumption of trade. Following the pattern of leaders such as Taharqo, the co-regents pursued an ambitious campaign of building, renovating, and expanding temples throughout Nubia.

The remains of the temple complex the co-regents are associated with in Dangeil suggest that it must have been stunning. A monumental gate facing the Nile measured roughly 100 feet across. Inside, a processional way was lined with sandstone sculptures of kneeling rams, which were strongly associated with Amun in Nubia.

There, the god was portrayed with a ram’s head, having been amalgamated with indigenous ram-headed gods when he was imported from Egypt, where he was generally portrayed with a human head. Along the processional way was a kiosk where Amun—in the form of the temple’s ram-headed cult statue carried by priests in a sacred barque—would rest on trips out of the temple sanctuary during festivals. These festivals featured large crowds and allowed common people, who were barred from the temple sanctuary, to revel in the presence of the god.

Historical Dictionary of the Sudan – Page 421 – Google Books Result

Fragments of this altar discovered by the archaeologists were inscribed with cartouches containing Queen Amanitore’s name.

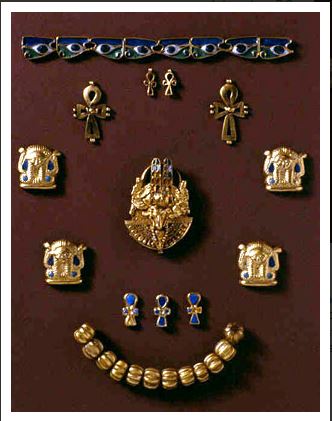

Jewelry from the tomb of Queen Amanishakheto in Meroë

–The Ancient Sudan: (Society for the Promotion of the Egyptian …

Behind the temple, archaeologists have found evidence that the complex drew worshipers in large numbers.

Guide to Egypt and the Sudan: Including a Description of the Route …

In just a small trench, they have found more than a million fragments of cone-shaped ceramic molds used to make offerings to Amun. Based on a count of mold bases, at least 77,000 such offerings are in evidence.

Despite its once formidable appearance and popularity among the public, the first-century A.D. temple to Amun was eventually destroyed in a large fire that was preceded by looting and smashing of the altars. “The looters dug a hole through the sanctuary floor—perhaps they were looking for gold or treasure,” says Anderson. “The ram statues are also smashed into tiny little pieces, so it looks as if a group of people came, looted the temple, smashed stuff up, and then may have set it on fire.”

Evidence suggests that the god continued to be worshipped in Nubia for several centuries after the fall of the Meroitic kingdom—that is, until the Byzantines introduced Christianity in the sixth century A.D.

Source: archaeology.org/issues/174-1505/features/3146-sudan-nubia-dangeil-cult-of-amun-ra

Subscribe

Archaeology – Archaeology Magazine

Key sites around Dangeil include a large fortress dated to the 4th-5th century AD, and an extensive tumuli field of the same date, extending over 3km and containing several hundred burial mounds. One of the most outstanding and substantial archaeological sites in the area is a Late Kushite city (3rd century BC – 4th century AD) situated within the modern village of Dangeil.

Late Kushite culture, as represented by Dangeil city, exhibits a rich mixture of Pharaonic, Graeco-Roman and indigenous African characteristics. This richness is related to the broad cultural contacts of the Kushite Empire. Throughout its existence (9th century BC – 4th century AD), the empire maintained close relations with Egypt, but at its zenith, in the 8th century BC, its dominion stretched from the borders of Palestine possibly as far as the Blue and White Niles and united the Nile valley from Khartoum to the Mediterranean.

Map Of Nubia Today

Many mounds stand over 4m high. After excavation we discovered that each mound was in fact an individual, well-preserved building.

Our excavations began on one of the large mounds, known as Kom H, in the centre of the site. Initially, we uncovered a red brick surface, which we thought to be a floor; however, it was quickly realized that we were in fact standing on the uppermost part of a building.

The Kushites believed that the home of the god Amun was in the mountain of Jebel Barkal, near the 4th Nile Cataract.

King Taharqo is the most famous, and is mentioned in the Bible.

However, after ruling for around a hundred years in the 8th century, the Kushites were expelled from Egypt by the Assyrians. Nonetheless, the Kushite kingdom flourished in Sudan for another 1000 years, remaining powerful, and maintaining close contacts with Egypt.

The walls are largely built of red and mud bricks and the roof was held up by columns with drums made of red brick quarters or thirds.

Carefully laid sandstone flagstones of varying sizes were used as flooring in the central corridor, its second court and sanctuary.

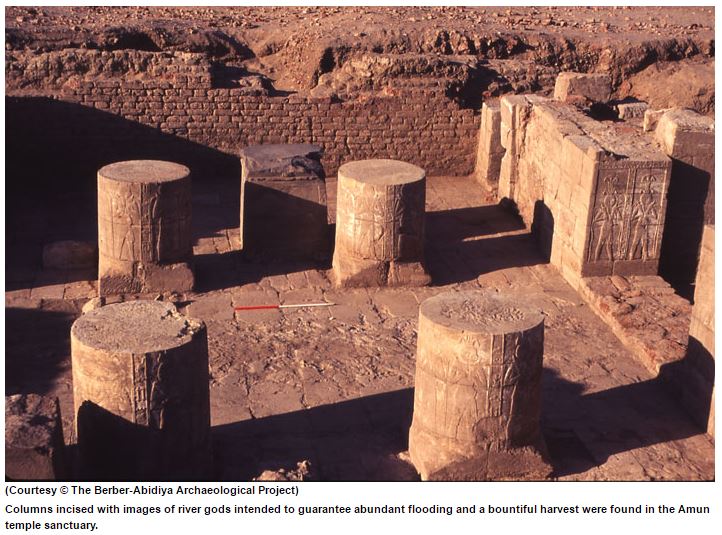

The local written language of the Kushites, and is yet to be deciphered. As for the footprint, we often find images of feet or sandals inscribed in or near to holy places, created as a marks or expressions of piety, during the Late Kushite period. The sanctuary was buried beneath fallen sandstone blocks and pieces of the chapel facings. With the sanctuary exposed, four decorated sandstone columns, and two altars were visible along with three chapels. Unlike the rest of the temple, the sanctuary columns consist of sandstone drums stacked one upon the other, with a thin paste of mud mortar sealing them together

Each is decorated with eight fertility figures striding forwards toward the main altar. Each figure wears a headdress of Nile plants and carries two jars from which are pouring offerings of water or milk to Amun. One of the altars was also decorated with these fertility figures. Moreover, from within the temple sanctuary we found painted wall plaster fragments containing a vertical column of Meroitic hieroglyphs along with portions of the lotus flower headdress and hair of a fertility figure. It appears that fertility figures pouring offerings were painted in the lower register of the sanctuary walls, presumably striding towards the main altar, just as their counterparts on the columns do. Pieces of painted plaster found on and within the mound suggested that the temple and associated buildings had once been brightly decorated.

The remains of three altars and a raised dais were discovered within the Dangeil temple.

–World Archaeology – Dangeil, Sudan

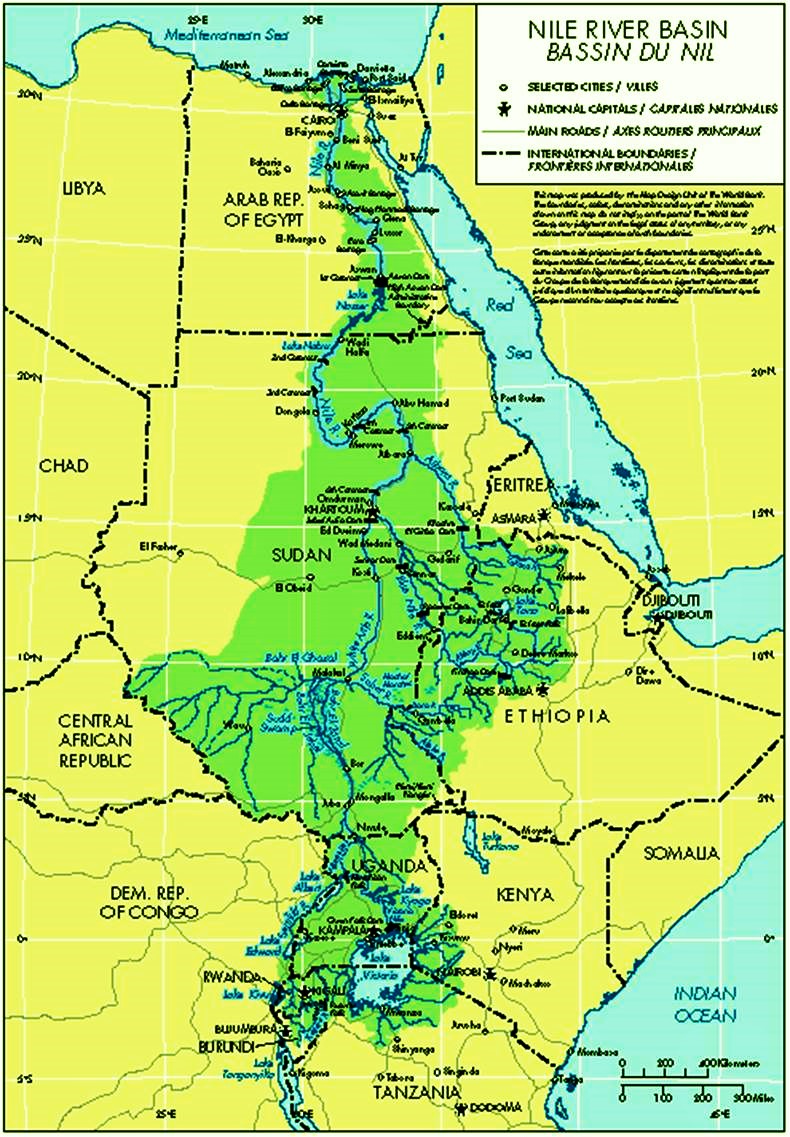

The Nile River is an international river

The Nile River is an international river that flows through 11 countries that include Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan and Egypt.

No Comments Yet