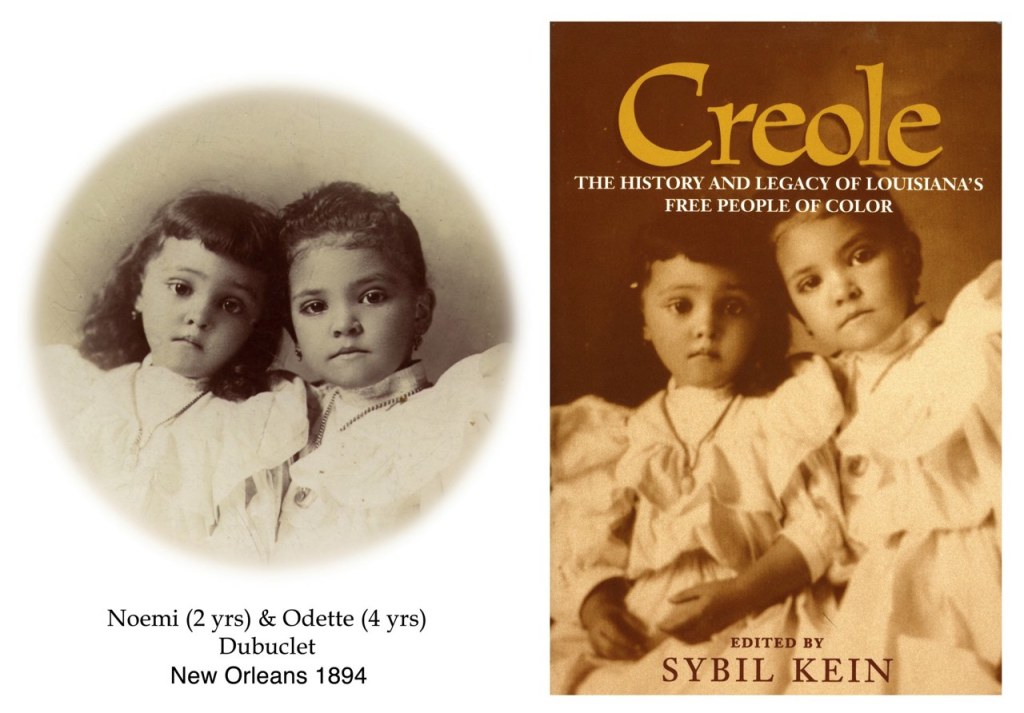

Many Creoles, however, are descendants of French colonials who fled Saint-Domingue (Haiti) for North America’s Gulf Coast when a slave insurrection (1791) challenged French authority. According to Thomas Fiehrer’s essay “From La Tortue to La Louisiane: An Unfathomed Legacy,” Saint-Dominque had more than 450,000 black slaves, 40,000 to 45,000 whites, and 32,000 gens-decouleur libres, who were neither white nor slaves. The slave revolt not only challenged French authority, but after defeating the expeditionary corps sent by Napoleon, the leaders of the slaves established an independent country named Haiti.

http://www.amazon.com/Creole-History-Legacy-Louisianas-People/dp/0807126012

Most Whites were either massacred or fled, many with their slaves, as did many mulatto freemen, many of who also owned slaves. By 1815, over 11,000 refugees had settled in New Orleans.

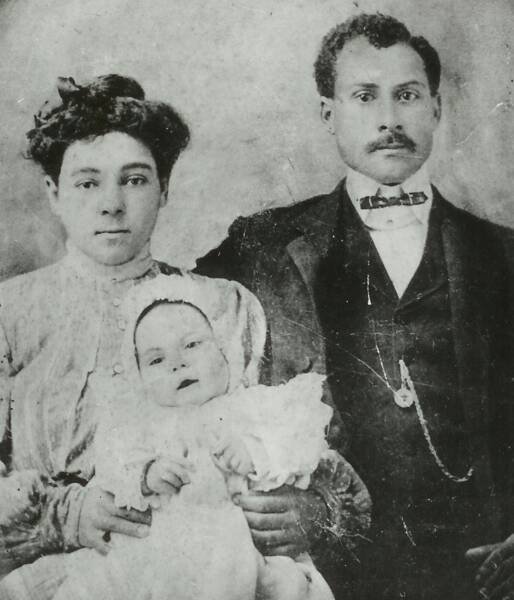

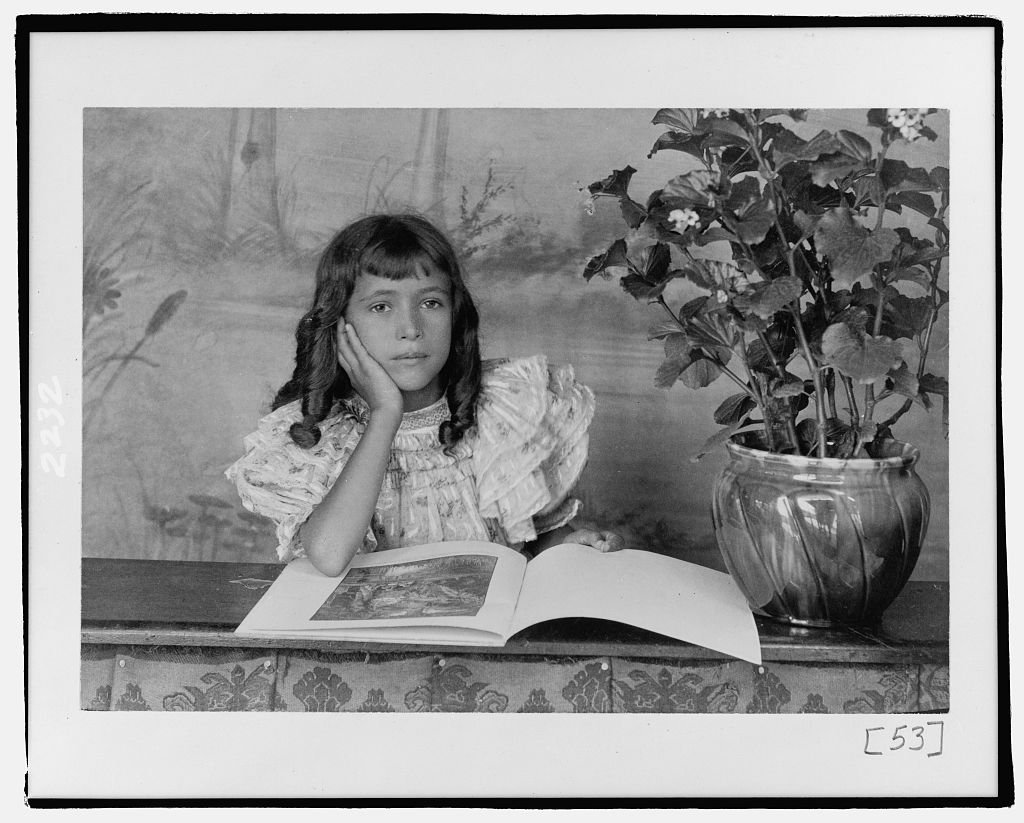

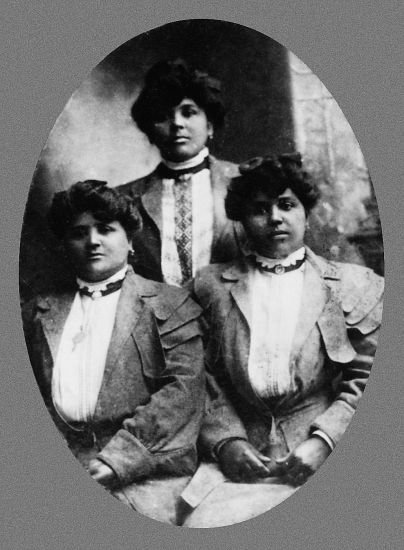

The ‘white’ slave children of New Orleans: Images of pale …

In Louisiana, the term Creole came to represent children of black or racially mixed parents as well as children of French and Spanish descent with no racial mixing. Persons of French and Spanish descent in New Orleans and St. Louis began referring to themselves as Creoles after the Louisiana Purchase to set themselves apart from the Anglo-Americans who moved into the area. Today, the term Creole can be defined in a number of ways. Louisiana historian Fred B. Kniffin, in Louisiana: Its Land and People, has asserted that the term Creole “has been loosely extended to include people of mixed blood, a dialect of French, a breed of ponies, a distinctive way of cooking, a type of house, and many other things. It is therefore no precise term and should not be defined as such.”

Take care of your body, it's the only

Take care of your body, it's the only