The Minoans may have first come into contact with Africans at Thebes, during the periodic bearing of tribute to the pharaoh. In fact, paintings in the tomb of Rekhmire, dated to the fourteenth century B.C., depict African and Aegean peoples, most likely Nubians and Minoans. However, with the collapse of the Minoan and Mycenaean palaces at the end of the Late Bronze Age, trade connections with Egypt and the Near East were severed as Greece entered a period of impoverishment and limited contact.

Archaeologist Manfred Bietak conducted extensive research on ancient Greek civilizations and their connections to ancient Egypt. Bietak unearthed evidence from artwork as early as 7000 B.C. that depicts the early people inhabiting Greece were of African descent.

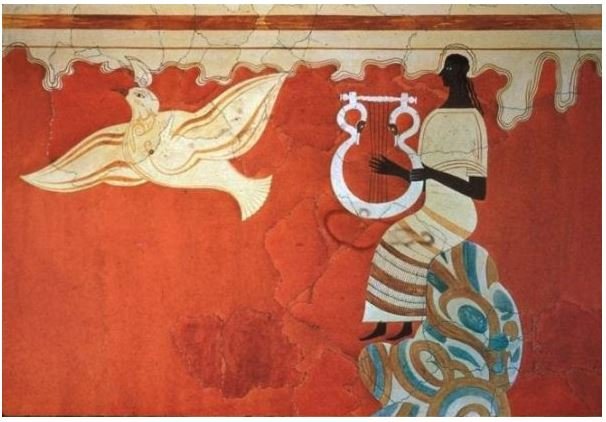

The Minoan culture of Ancient Greece reached its peak at about 1600 B.C. They were known for their vibrant cities, opulent palaces and established trade connections. Minoan artwork is recognized as a major era of visual achievement in art history. Pottery, sculptures and frescoes from the Minoan Bronze age grace museum displays all over the world. Palace ruins indicate remnants of paved roads and piped water systems.

–A.B.S.

Tales of Ethiopia as a mythical land at the farthest edges of the earth are recorded in some of the earliest Greek literature of the eighth century B.C., including the epic poems of Homer. Greek gods and heroes, like Menelaos, were believed to have visited this place on the fringes of the known world. However, long before Homer, the seafaring civilization of Bronze Age Crete, known today as Minoan, established trade connections with Egypt.

They said they found 2,500-year-old African people sculptures in the village. If I tell them that I’m a descendant of Democritus, they are going to freak out, because Greece didn’t even exist back when I got my Greek roots.

Thank you for sharing!

During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., the Greeks renewed contacts with the northern periphery of Africa. They established settlements and trading posts along the Nile River and at Cyrene on the northern coast of Africa. Already at Naukratis, the earliest and most important of the trading posts in Africa, Greeks were certainly in contact with Africans. It is likely that images of Africans, if not Africans themselves, began to reappear in the Aegean. In the seventh and early sixth centuries B.C., Greek mercenaries from Ionia and Caria served under the Egyptian pharaohs Psametikus I and II.

All black Africans were known as Ethiopians to the ancient Greeks, as the fifth-century B.C. historian Herodotus tells us, and their iconography was narrowly defined by Greek artists in the Archaic (ca. 700–480 B.C.) and Classical (ca. 480–323 B.C.) periods, black skin color being the primary identifying physical characteristic. It is recorded that Ethiopians were among King Xerxes’ troops when Persia invaded Greece in 480 B.C. Thus, the Greeks would have come into contact with large numbers of Africans at this time.

Nonetheless, most ancient Greeks had only a vague understanding of African geography. They believed that the land of the Ethiopians was located south of Egypt. In Greek mythology, the pygmies were the African race that lived furthest south on the fringes of the known world, where they engaged in mythic battles with cranes (26.49).

Ethiopians were considered exotic to the ancient Greeks and their features contrasted markedly with the Greeks’ own well-established perception of themselves. The black glaze central to Athenian vase painting was ideally suited for representing black skin, a consistent feature used to describe Ethiopians in ancient Greek literature as well. Ethiopians were featured in the tragic plays of Aeschylus, Sophokles, and Euripides; and preserved comic masks, as well as a number of vase paintings from this period, indicate that Ethiopians were also often cast in Greek comedies.

Well into the fourth century B.C., Ethiopians were regularly featured in Greek vase painting, especially on the highly decorative red-figure vases produced by the Greek colonies in southern Italy (50.11.4). One type shows an Ethiopian being attacked by a crocodile, most likely an allusion to Egypt and the Nile River. Depictions of Ethiopians in scenes of everyday life are rare at this time, although one tomb painting from a Greek cemetery near Paestum in southern Italy shows an Ethiopian and a Greek in a boxing competition.

With the establishment of the Ptolemaic dynasty and Macedonian rule in Egypt, after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., came an increased knowledge of Nubia (in modern Sudan), the neighboring kingdom along the lower Nile ruled by kings who resided in the capital cities of Napata and later Meroe. Cosmopolitan metropolises, including Alexandria in the Nile Delta, became centers where significant Greek and African populations lived together.

During the Hellenistic period (ca. 323–31 B.C.), the repertoire of African imagery in Greek art expanded greatly. While scenes related to Ethiopians in mythology became less common, many more types occurred that suggest they constituted a larger minority element in the population of the Hellenistic world than the preceding period (18.145.10). Depictions of Ethiopians as athletes and entertainers are suggestive of some of the occupations they held. Africans also served as slaves in ancient Greece (74.51.2263), together with both Greeks and other non-Greek peoples who were enslaved during wartime and through piracy. However, scholars continue to debate whether or not the ancient Greeks viewed black Africans with racial prejudice.

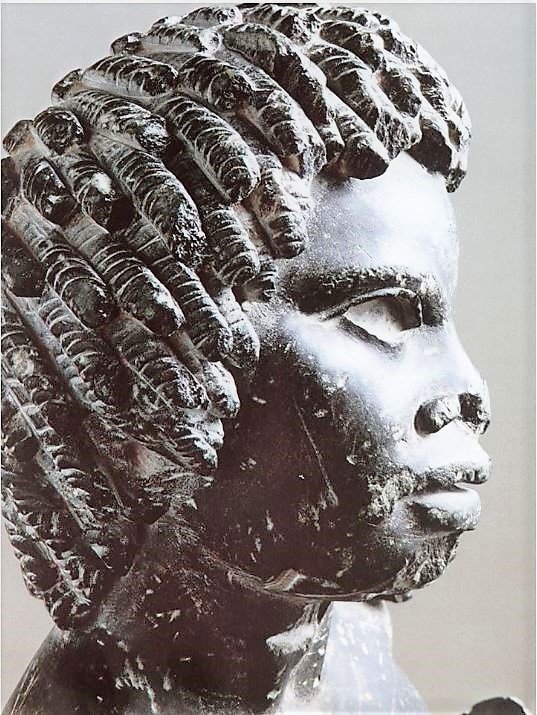

Large-scale portraits of Ethiopians made by Greek artists appear for the first time in the Hellenistic period and high-quality works, such as images on gold jewelry and fine bronze statuettes, are tangible evidence of the integration of Africans into various levels of Greek society.

–Africans in Ancient Greek Art | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History …

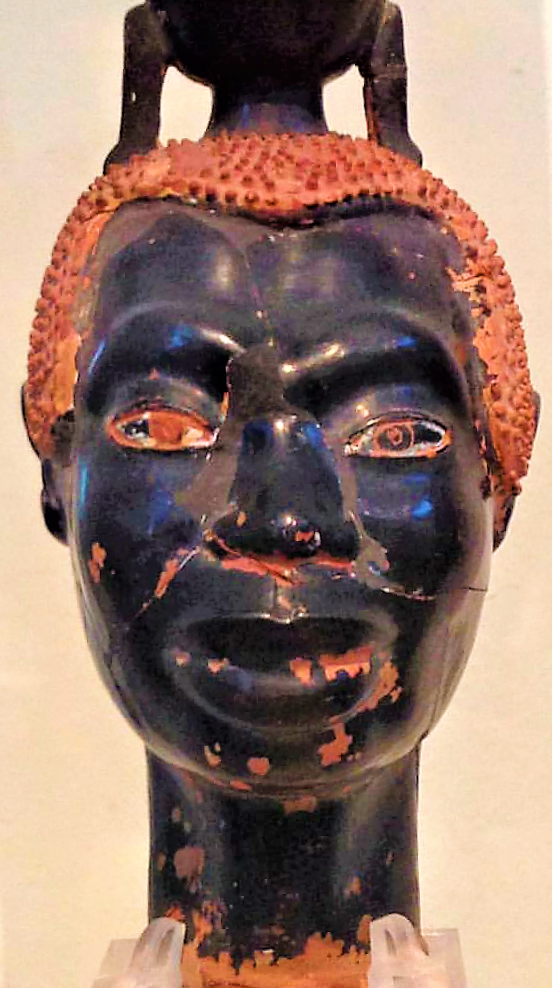

–Unknown greek ceramicists Attic plastic vases in the image of a black male. Greece (c. 500 BCE)

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

–Young African in Hellenistic Greece. National Museum in Athens, Greece.

journeytothesource.info/black_athena

Thanks for sharing!

Examines the claims of Professor Martin Bernal who questions the assumption of the “Europeaness” of our civilization placing instead the “black” Egyptians and Phoenicians at the center of the West’s origins. Black Athena examines Cornell Professor Martin Bernal’s iconoclastic study of the African origins of Greek civilization and the explosive academic debate it provoked. This film offers a balanced, scholarly introduction to the disputes surrounding multiculturalism, “political correctness” and Afrocentric curricula sweeping college campuses today. In his book Black Athena, Prof. Bernal convincingly indicts 19th-century scholars for constructing a racist “cult of Greece” based upon a purely Aryan origin for Western culture. He accuses these classicists of suppressing the numerous connections between African and Near Eastern cultures and early Greek myth and art. Leading classical scholars, on the other hand, contend that Bernal, like the 19th-century classicists he attacks, uses evidence selectively, uncritically and ahistorically to support his own Afrocentric agenda. They argue that cultural diffusion alone can’t account for the distinctive achievements of the Greeks during the Classical Period. Black Athena can help students begin to distinguish between sound scholarship and cultural bias – whether inherited from the past or imposed by the present.

Ancient Faces: Romano-Egyptian Mummy Portrait of a Bearded Man

–Greek (Apulian), Head Vase in the form of an African noble, mid-to-late fourth century BC (ca. 350–320 BC), terracotta, 9½”high. Located at & Photo Courtesy of [Virginia Museum of Fine Arts]

The Dry bones shall rise again! Today, we have see the Original Melanin People as the source for Greek, Roman, Medo-Persian Civilization. We are the Cradle of Civilization! Sola, thank you for your work. Do you believe that The Dry Bones will rise again?

[…] Africans in Greece […]