Credo Mutwa speaks of magnificent unexplored stone sites, ancient people, giants, gods, ancient travelers and astronomy in South Africa.

The term “shamanism” was first applied by western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighboring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some caucasian anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense, to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.

His father was a widower with three surviving children when he met his mother. His father was a builder and a Christian and his mother was a young Zulu girl. Caught between Catholic missionaries on one hand, and a stubborn old Zulu warrior, Credo Mutwa’s maternal grandfather, his parents had no choice but to separate. Credo was born out of wedlock, which caused a great scandal in the village and his mother was thrown out by her father. Later he was taken in by one of his aunts.

He was subsequently raised by his father’s brother and was taken to the South Coast of Natal (present day KwaZulu-Natal), near the northern bank of the Mkomazi River. He did not attend school until he was 14 years old. In 1935 his father found a building job in the old Transvaal province and the whole family relocated to where he was building.

After falling severely ill, he was taken back to KwaZulu-Natal by his uncle. Where Christian doctors had failed, his grandfather, a man whom his father despised as a heathen and demon worshipper, helped him back to health. At this point Credo began to question many of the things about his people the missionaries would have them believe. “Were we Africans really a race of primitives who possessed no knowledge at all before the white man came to Africa?” he asked himself. His grandfather instilled in him the belief that his illness was a sacred calling that he was to become a sangoma, a healer. He underwent thwasa (sangoma training and initiation) with his grandfather and mother’s sister, a young sangoma named Mynah.

Credo Mutwa speaks of magnificent unexplored stone sites, ancient people, giants, gods, ancient travelers and astronomy in South Africa.

Thank you for sharing!

Mircea Eliade writes, “A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = ‘technique of religious ecstasy‘.” Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.

Beliefs and practices that have been categorized this way as “shamanic” have attracted the interest of scholars from a wide variety of disciplines, including anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, religious studies scholars, philosophers, and psychologists. Hundreds of books and academic papers on the subject have been produced, with a peer-reviewed academic journal being devoted to the study of shamanism. In the 20th century, many westerners involved in the counter-cultural movement have created modern magico-religious practices influenced by their ideas of indigenous religions from across the world, creating what has been termed neoshamanism or the neoshamanic movement. It has affected the development of many neopagan practices, as well as faced a backlash and accusations of cultural appropriation, exploitation and misrepresentation when outside observers have tried to represent cultures they do not belong to.

In Mali, Dogon sorcerers (both male and female) communicate with a spirit named Amma, who advises them on healing and divination practices.

The classical meaning of shaman as a person who, after recovering from a mental illness (or insanity) takes up the professional calling of socially recognized religious practitioner, is exemplified among the Sisala (of northern Gold Coast) : “the fairies “seized” him and made him insane for several months. Eventually, though, he learned to control their power, which he now uses to divine.”

The term sangoma, as employed in Zulu and congeneric languages, is effectively equivalent to shaman. Sangomas are highly revered and respected in their society, where illness is thought to be caused by witchcraft, pollution (contact with impure objects or occurrences), bad spirits, or the ancestors themselves, either malevolently, or through neglect if they are not respected, or to show an individual her calling to become a sangoma (thwasa). For harmony between the living and the dead, vital for a trouble-free life, the ancestors must be shown respect through ritual and animal sacrifice.

The term inyanga also employed by the Nguni cultures is equivalent to ‘herbalist’ as used by the Zulu people and a variation used by the Karanga, among whom remedies (locally known as muti) for ailments are discovered by the inyanga being informed in a dream, of the herb able to effect the cure and also of where that herb is to be found. The majority of the herbal knowledge base is passed down from one inyanga to the next, often within a particular family circle in any one village.

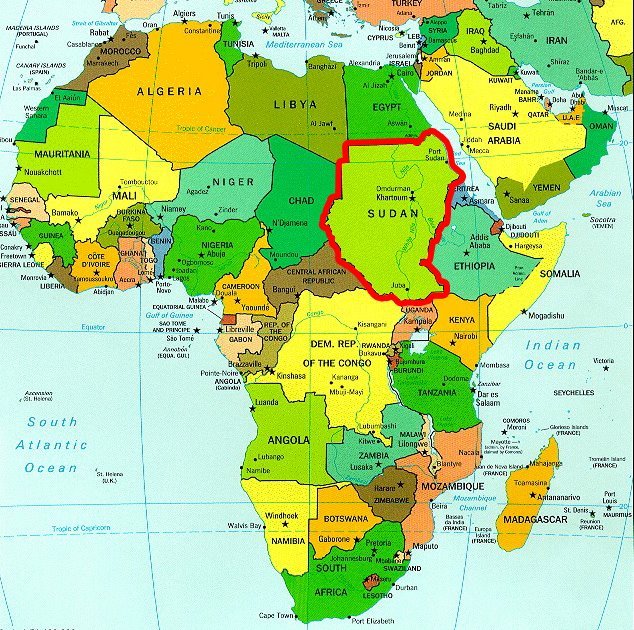

Map Of Sudan

Shamanism is known among the Nuba of Kordofan in Sudan.

Nuba is a collective term used here for the various indigenous peoples who inhabit the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan state, in Sudan. Although the term is used to describe them as if they composed a single group, the Nuba is an umbrella term encompassing multiple distinct peoples that speak different languages, often belonging to unrelated language groups. Estimates of the Nuba population vary widely; the Sudanese government estimated that they numbered 1.07 million in 2003.

Most of the Nuba peoples speak one of the many languages in the geographic Kordofanian languages group of the Nuba Mountains. This language group is in the major Niger–Congo languages family. Several Nuba languages are in the Nilo-Saharan languages family.

Over one hundred languages are spoken in the area and are considered Nuba languages, although many of the Nuba also speak Sudanese Arabic, the official language of Sudan.

No Comments Yet